Preserving Burundian Heritage Basketry Skills Among Refugees

In Esperance Balingayao’s Burundian upbringing, learning basketry came early, “my mother taught me how to weave when I was thirteen years old”, she recalls.

Basket weaving remains one of the most long-standing art forms in East Africa. The enduring role of baskets and the basketry tradition has resulted in an art form that serves both a utilitarian function and aesthetic beauty. Baskets are used for all sorts of purposes: storing grain, flour and small household objects. Baskets are also used in weddings and other celebrations - they are placed on the head and used to carry presents to the event for the bride and groom.

Sisal is a sustainable natural fibre carefully cultivated from the agave plant’s long, green leaves. Known for its strength, durability, and texture, sisal is extracted, sun-dried, brushed, and baled by local farmers across Rwanda before being handwoven into baskets and bags. Because sisal groves generate mostly organic waste, leftover materials are also used to produce animal feed, electricity, and fertilizer. © Indego Africa

Esperance, a Burundian refugee weaving baskets with the support of WomenCraft. ©WomenCraft

In recent decades, handmade basketry is increasingly replaced by plastics made containers. As a result, this heritage craft is less invested in everyday objects. However, for Burundian refugees, artisan skills are proving invaluable to helping create economic security in the face of unimaginable hardship.

Since 2015, political unrest in Burundi has driven hundreds of thousands of its people to neighbouring countries in search of safety. Esperance was among those forced to flee, seeking safety across the border in a refugee camp. By tapping into her heritage basketry skills she found a way to help support herself and her family when other income opportunities were scarce. “Today, I am so happy to have an income through my weaving”, she remarked. Esperance is not alone.

WomenCraft, Fair Trade certified social enterprise in Ngara in the remote northeast of Tanzania, work with Burundian women who recently returned to their home living along the border of their country. Their mission is to increase economic opportunity in the post-conflict, tri-border area of Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania by bringing rural women together, facilitating their growth and connecting their artistry to the global marketplace. Since their founding in 2007, over 600 artisans got to advance themselves, raise stronger families, and stimulate their communities.

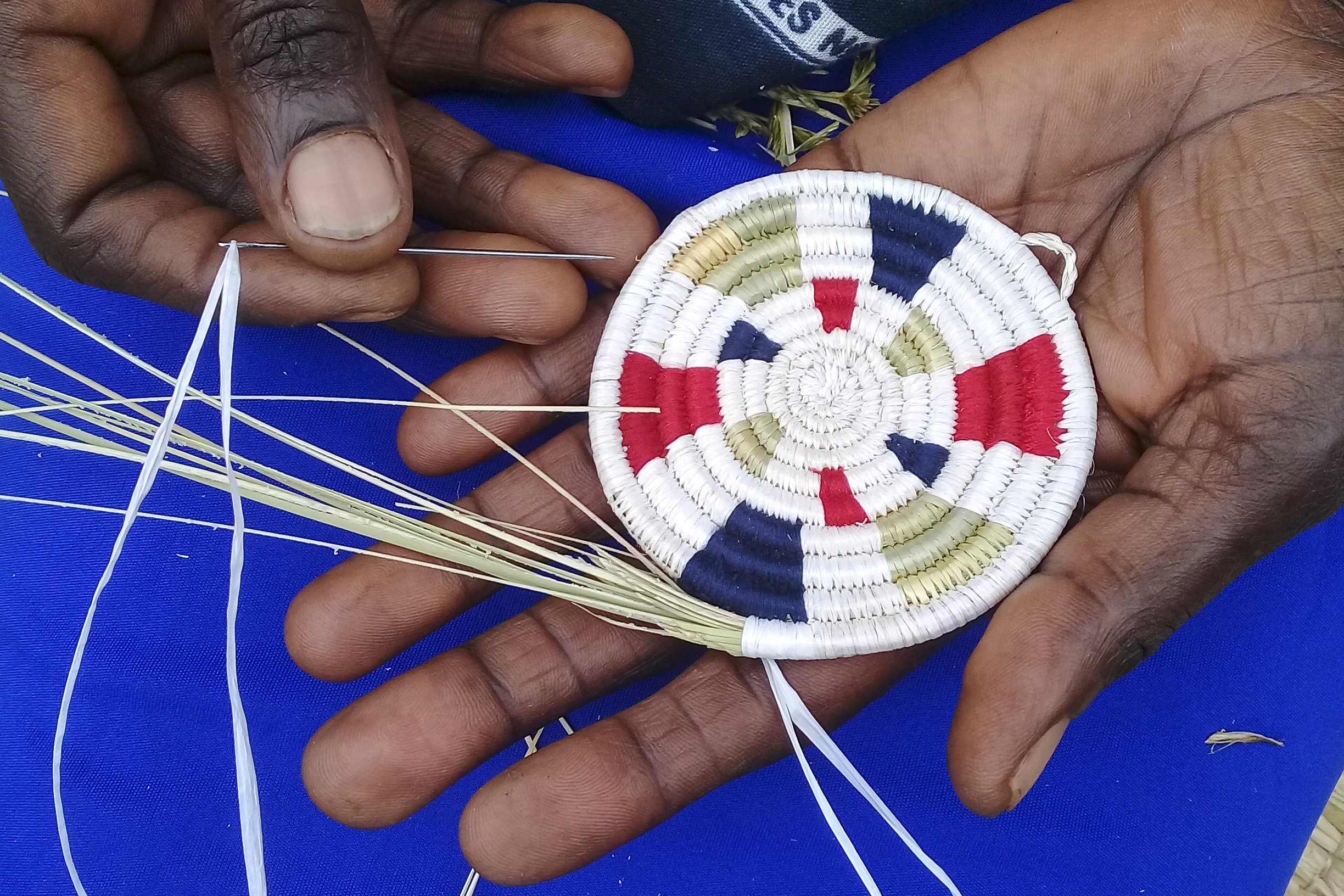

To craft a WomenCraft basket, sweetgrass strands are bundled together and bound with soft hand-dyed sisal fibre or fibres from grain sacks. As the length of the bundle is wrapped, sweetgrass strands are fed into it, and it is worked into a spiral. As work progresses, these wrapped coils are layered upon one another, forming the walls of a basket. Alongside functional full-sized pieces, these iconic shapes are now being made in miniature as part of the MADE51 holiday ornament.

Sweetgrass, raw materials of basket weaving. ©WomenCraft

Upcycled gunia grain sacks as raw materials for weaving. ©WomenCraft

Featured in our previous story, Indego Africa is another social enterprise working with Burundian artisans in Rwanda, providing opportunities for them to earn an income while preserving time-honoured artisanal traditions.

It is a virtuous circle. Marie Rose Nyabenda, a Burundian refugee in Rwanda, reflected on her experience, “I’ve learned so many new things about being an artisan and working together in a cooperative.” For her, the next step is passing that knowledge onwards. “Now, I wish to train my children how to weave and save money so they can be creative and empowered too.”

Work in progress ornament ‘Radiant Circle’. ©WomenCraft

Naimaana, Mukamaana and Maria, Burundian refugees who weave with WomenCraft. ©WomenCraft

For Mukamaana (above right), a mother of 5, weaving with WomenCraft was her only option to earn an income when she was living in Mtendeli refugee camp in Tanzania. Practising the heritage craft is something that she reported enjoying greatly, for it enabled exchanging ideas with fellow artisans and forming a support network to cope with the daily struggles in the camp. She was able to save up enough from basket weaving that when refugees were prohibited from economic activity by the government, she was able to make the choice to return to Burundi and restart her life. Her friend, Naimaana, also saved up - enough to build a new house upon her return.

A sign of the opportunity that weaving has brought them? These two women, and many others, decided to return to the nearby border region so that they could continue to work with WomenCraft. Their speciality is weaving using natural grass and recycled grain sacks, leftovers from food distribution in the camps. The story and sustainability of their pieces are a major draw for global buyers.

One of their most beloved designs, the Ikiba pattern, is presented in a tiny version as an ornament. Stemming from the word “Ikibano”, it represents the refugee population as a community with a shared background and determination to be united and overcome the challenges of being a refugee. This ‘Radiant Circle’ thus represents the new opportunities returning refugees have as they build their new lives (above left).

Esperance Butoyi making the ‘Rising Sun’ ornament. ©Indego Africa

Burundian women making the ‘Radiant Circle’ ornament. ©WomenCraft

Artisans working with Indego Africa in Rwanda’s Mahama and Kigeme Refugee Camps are also putting their skilful hands to work creating an ornament, the Rising Sun. Woven with hand-dyed sisal and sweetgrass in light blue and red accent colours, these mini sweetgrass baskets bring a message of courage: the design represents the additional strength and persistence needed to rise again after being forced from home.

The meaning is well taken by the weavers - most of them are the primary earners of their families, who save 10% of their income from weaving according to Indego Africa. Their saving practice plays an important role in helping families to ride through the COVID financial shocks, particularly during the initial phase of the pandemic. View the original article on the MADE51 blog.