Anni Albers – Weaving a discipline of resilience

Anni Albers (1899-1994) is the chosen artist to celebrate the Bauhaus centenary year at Tate Modern. The retrospective exhibition, Anni Albers, explores the pioneering female artist’s position within the history of abstract modernism and puts weaving in the spotlight. “It’s an opportunity for Tate to recognise a female artist whose name is still missing from many art history textbooks, who remains forever associated with her husband Josef, and whose discipline, textile, is still being sidelined by the world’s major museums.” expressed Ann Coxon, curator of displays and international art at Tate Modern (1).

Visitors of the exhibition are greeted by Albers’s loom, her instrument, at the entrance. The rest of the displays proves the magic it is capable of making under Anni Albers’s hands: a rich collection of ‘pictorial weavings’, wall-hangings, and architectural fabrics. Despite her body being deliberately absent throughout the exhibit to let the textiles speak for themselves, the works effectively communicate her philosophy and engage with the audience in a tangible way. Her committed practice was only hinted by a contemporary weaving video that signified time-marking and the ageing of the body at the exit of the exhibition. This essay responds to the Tate Modern’s exhibition and The Event of a Thread: Anni Albers conference by examining how Albers as an overlooked Bauhaus artist wove a legacy of resilience through rethinking, reinventing, rebranding and reorienting weaving practice.

Since the start of her artistic pursuit at the Bauhaus in Weimar in 1922, Albers, being a female, has been hindered in the male-dominated art scene. Although originally desiring to become a painter, she was rejected by a few fine art disciplines and eventually enrolled in the school’s weaving workshop. Years later she reflected on the encounter with shared the same prejudice, “In my case, it was threads that caught me, really against my will. To work with threads seemed sissy to me. I wanted something to be conquered. But circumstances held me to threads and they won me over.” (2). Evidence from Bauhaus’s catalogue from that period until today, textile art is seen as a second-class medium and struggles to be recognised as mainstream art (3). As a female and a weaver, she was double marginalised; yet the opposition she faced guided her revolutionary career.

Albers was awarded her diploma in 1930 and took over the running of the weaving workshop in the following year. In 1933, Josef and Anni Albers moved to the United States in response to an invitation to teach at the Black Mountain College in North Carolina. The progressive and experimental college provided an incomparably creative and intellectual atmosphere, where Albers served as Assistant Professor of Art until 1949. She built up the weaving workshop while Josef Albers took a crucial role in leading the educational focus of the college. These years were inaugurate of her productive and influential weaving legacy.

Rethinking the grid

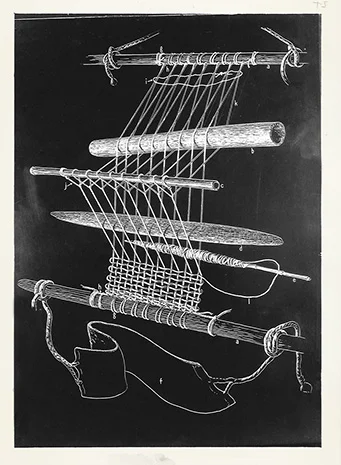

‘The loom, the hand-weaver’s instrument, has many and variable parts. […] We imagine the weaving process as a rhythmic side-to-side bodily motion in which the weaver passes the weft threads between the warp threads from left to right and right to left, building up a plane of fabric between two fixed points. The action evokes playing the piano or other musical instrument[s].’ – Brenda Danilowitz (4).

A weaver always has to think structurally instead of simply designing the patterns that appear on the woven surface (5). As the loom becomes an extension of the weaver’s working body, weaving is embodied in her intellectual and physical capacities. What made Albers a philosophical weaver were her attempts to work against the grid. It is impossible for someone as creative as her to be restricted to a form that was pre-set by someone else. If the loom was to be her tool, she needed to bring forms into an agreement to the structure law (6). She deconstructed the gendered politics of the weaving industry, where men often involve with an industrialised mechanical aspect of weaving and women rooted in pre-loom practice and thread making, by perfecting the manipulation of the loom. Her cross-influences with her friend and composer John Cage was a good example, where the two exercised experimental customisation to the loom and the piano. While Cage composed with screws on the piano strings, Albers also challenged her instrument with techniques such as supplementary wefts weaving, composing an alternative round of the weaving process beyond rhythmic shuttle flying. Albers’s Black White Gold I, 1950 was a gift to Cage, showing many similar visual inspirations with the composer’s score page sample (6).

As Albers mastered her instrument, she injected freedom into the grid. Josef and Anni Albers’s fascination in the pre-Columbian culture led them to visits across Mexico, Peru and Chile, where Albers studied in depth the weaving with backstrap looms from the ancient civilisations (7). Backstrap looms are the most down to earth weaving instruments used by women across the world. Balancing body movements and the few pieces of personally shaped wooden pieces, it is only complete with the body and pushes the boundaries of a pre-set grid. Albers’s choice of adopting and teaching with these looms was the best illustration of challenging the structures and advancing freedom in her weaving. Her inventive approach to each stage of the textile making was an act against the concept of division of labour, seeing the loom is not a mechanical tool to perform based on set guidelines, but that it is part of the body, an instrument for the weaver’s artistic expression.

Reinventing materiality

Albers kept an intimate relationship with the materials. Across the work of her lifetime, she redefined thread-making with unconventional components, and reinterpreted mathematical theories and ancient texts with new technical weaving.

In 1929, when the Bauhaus won a commission for the Trade Union School in Bernau, Germany, Albers developed a collection of textiles for the Hannes Meyer’s auditorium, incorporating various types of synthetic fibres and cellophane to create acoustic panels. Her research on these sound-absorbing materials influenced the manufacturing and new innovations in theatre design (8). During her teaching at Black Mountain College, where the rural environment provided plenty of natural materials, Albers encouraged her students to experiment with new sensory balances using textures such as grass, paper, corn kernels and metal shavings to explore "the stuff the world is made of", as she put it (9). Her sensibility to a haptic and tactile experience in weaving has resulted in the involvement in thread makings and manipulations both on and off the loom.

Combined Paul Klee’s teachings at the Bauhaus with her study of textiles and ideographic signs of the ancient world, Albers incorporated linguistic characters and systems into her weavings, intending them to be read visually with semiology (10). She understood that the Pre-Columbian textiles were made for communication, especially in Peru, where there was no written language. Ancient Writing (1935) was the first in a series of Albers’s pictorial weavings, including Haiku (1961), Code (1962) and Epitaph (1968), whose titles refer specifically to texts and coded or ciphered character languages (11).

‘To let threads be articulate again and find a form for themselves to no other end than their own orchestration, not to be sat on, walked on, only to be looked at…’ – Anni Albers (12)

Albers made clear that her pictorial weavings are to be considered works of art, a tactic to address the Beaux Arts hierarchy by putting textiles and crafts in the fine art category. These works displayed what the artist described as ‘a form of weaving that is pictorial in character, in contrast to pattern weaving, which deals with repeats of contrasting areas’ (13). In short, they are artworks made by the materials and processes of weaving. Take Red and Blue Layers (1954) as an example of technical and artistic triumph, Albers used the technique known as leno or gauze weave, where the vertical wraps twist over each other around the horizontal wefts.

Perhaps one of her most impressive pictorial weavings which can be read through semiotics was Six Prayers (1966-7), a piece that was commissioned by the Jewish Museum, New York to create a memorial to the six million Jews who had been killed in the Holocaust. She took the opportunity to create an ‘architectural’ tapestry to consider the form and function of the Torah scrolls with their Hebrew script. The 6 panels in a sombre palette of grey and beige cotton and linen threads, highlighted by silver accents, each measuring 186 x 50 cm, were to be presented with spaces between them, intended for the memorial to be meditative rather than monumental. Critic Mark Stevens described the work as ‘six weavings resemble prayer shawls. The interlacing of discordant lines suggests both control and mayhem, darkness and light; human beings appear woven of good and evil on the loom of nature.’ (14). Despite the critic’s metaphorical and rather exaggerating interpretation, his reading revealed Albers’s intentional use of the luminous surfaces which created an optical effect. ‘Albers’s expertise in textile properties and technologies, and her understanding of their impact in a given space resulted with Six Prayers, in a memorial which is mindful of tradition yet unapologetically modern’ commented curator Ann Coxon (14).

Rebranding weaving practice

In 1950, Josef and Anni Albers moved to Connecticut, where Josef served as chairman of the Department of Design at the Yale University School of Art and Albers gave informal lectures at Yale architecture faculty from the late 1950s. As a textile artist and practitioner, Albers was not recognised by the art departments of most schools. Yet, she actively taught and wrote, publishing among all-male authors such as in the Yale Architectural Journal, Perspecta, in 1957. Albers’s writings were precise and authoritative, referencing established thoughts with words such as ‘principles’ and ‘fundamentals’ in her influential book On Weaving in 1965. In Perspecta, she described weaving as ‘engineering work of fabric construction’, referring threads with words like ‘strength’, ‘ability to bear tension’, and the loom as the ‘machine’ (15). In order to win textile a standing in the modern practice, Albers was careful with her choice of words to relate to her targeted readers. In this case, she rebranded weaving as a form of architecture, the field which she gained more recognition (16,17).

Albers worked on a number of architectural commissions, collaborating with modernist architects and designers. In 1944, she designed a striking half-wall, half-decorative drapery fabric with light-reflecting qualities as curtains for the Rockefeller Guest House in Manhattan, New York. She went on to design and develop a series of casement fabrics for Knoll from 1958 onwards, where the train-track weave acted as ‘an inconspicuous but highly effective non-solid filter’ as described by Briony Fer, co-curator of the Tate exhibition. Both works illustrated how Albers’s woven textiles came into a dramatic relationship with the surrounding architectural materials, in this case, the large glass windows in the post-war modern design (18). By seeing textiles as part of the building structure, Albers repositioned her practice through acute communications and rebranding it into an architectural component.

Reorienting as a functional discipline

As Albers created a space for textiles in architecture, she proved that her work was functional and accessible. During her time there, the Bauhaus school was led by a core circle of upper-class men. Robin Schuldenfrei argued that ‘While modernism was publicised as a fusion of technology, new materials, and rational aesthetics to improve the lives of ordinary people, it was often out of reach to the very masses it purportedly served’ (3). Seen from the 1925 school sample catalogue, the designs were achieved by handcrafting skills, hard to be reproduced by mass production, and were items that already had a place in the upper-class households (3).

As one of the few profitable workshops, the weaving workshop was regarded as essential to maintain for the Bauhaus Art School’s vision as a laboratory for industrial innovations (8). Furthermore, Albers’s commercial and innovation successes, seen in mentioned commission projects as well as the designs for the student dormitories for the Harvard Law Faculty in 1949. Albers’s designs were approachable and affordable, broadening social engagement with her textiles. In fact, she started giving samples to museums’ collections from the early 50s when no one was interested in textile art. To a certain extent, she took command of the historical records of this discipline (19).

While the Bauhaus Art School was a leading ideological and well connected institution, Albers was committed to teaching at the Black Maintain College with a practical and avant-garde approach, leaving a legacy of knowledge with her students. She reoriented the narrative of woven textile as both an art and a functional disciplines. ‘Her bold abstract compositions, with simple colour palettes, prove that woven design doesn’t need to be figurative or complicated to be beautiful. We’ve always been inspired by the breadth of her creativity and her ability to create striking woven textiles using standard woven techniques, pushing the ‘dobby shaft’ loom to its limits, as opposed to using a jacquard loom.’ said textile designer Wallace Sewell, giving her testimony on how Albers’s work has influenced her, among many other designers, since the open of the Tate exhibition (20).

As the exhibition addresses the long-running inequality in the discipline of modern art, Anni Albers allowed us to explore the world of this exceptional Bauhaus artist and how she wove a legacy through rethinking, reinventing, rebranding and reorienting her persistent practice. The exhibition closes with another loom, an eight-harness Structo Artcraft handloom, which Albers made many of her pictorial weavings on. Setting up the loom requires complex technique, patience and concentration. The only time in the exhibition where a weaver’s body made visible is in the nearby short film screening a contemporary weaver working in the coordinated rhythmic movement with the grid. It reminded of the hard, physical work demanded in weaving. The marking time with the sound of the loom signified how Albers spent her lifetime to weave a story of resilience in view of the challenges she faced. Albers hid behind her work, yet viewers got to know her intimately through reading signs in her weavings and texts and from the influences she had on contemporary textile artists.

Notes:

(1) Nayeri, F. (2018). At Tate Modern, an Anni Albers Retrospective. [online] Nytimes.com.

(2) Albers, A. (1982). The Art/Craft Connection: Grass Roots or Glass Houses at College Art Association’s 1982 annual meeting

(3) Schuldenfrei, R. (2018). Bauhaus Luxury. In: The Event of a Thread: Anni Albers conference.

(4) Danilowitz, B. (2018). Tangles, Knots, Braids, Loops and Links. In: A. Coxon, B. Fer and M. Müller-Schareck, ed., Anni Albers, 1st ed. London: Tate Publishing, pp.86-89.

(5) Fer, B. (2018c). Anni Albers: Weaving Magic. [online] Tate.

(6) Saletnik, J. (2018). Anni Albers, John Cage and “Attentive Passiveness”. In: The Event of a Thread: Anni Albers conference.

(7) Minera, M. (2018). Discovering Monte Alban. in A. Coxon, B. Fer and M. Müller-Schareck, ed., Anni Albers, 1st ed. London: Tate Publishing, pp.74-85.

(8) The Art Story. (2018). Anni Albers Overview and Analysis. [online]

(9) Fer, B. (2018b). Black Mountain College Exercises. in A. Coxon, B. Fer and M. Müller-Schareck, ed., Anni Albers, 1st ed. London: Tate Publishing, pp.64-73.

(10) Müller-Schareck, M. (2018). The Language of Thread. in A. Coxon, B. Fer and M. Müller-Schareck, ed., Anni Albers, 1st ed. London: Tate Publishing, pp.136-143.

(11) HALI. (2018). 'Anni Albers', Tate Modern, London - HALI. [online]

(12) Albers, A. (1959). Pictorial Weaving. Cambridge, MA: The New Gallery, Charles Hayden Memorial Library, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

(13) Tate. (2018). Anni Albers – Exhibition Guide. [online]

(14) Coxon. A. (2018). Temple Commissions and Six Prayers. in A. Coxon, B. Fer and M. Müller-Schareck, ed., Anni Albers, 1st ed. London: Tate Publishing, pp.144-151.

(15) Albers, A. (1957). The Pliable Plane; Textiles in Architecture. Perspecta, 4, p.36.

(16) Smith, T. (2018). Textile Principles: Adapting Anni Albers’s Philosophy. In: The Event of a Thread: Anni Albers conference.

(17) Troeller, J. (2018). Anni Albers as Architect. In: The Event of a Thread: Anni Albers conference.

(18) Fer, B. (2018a). Close to the Stuff the World is Made of: Weaving as a Modern Project. in A. Coxon, B. Fer and M. Müller-Schareck, ed., Anni Albers, 1st ed. London: Tate Publishing, pp.20-43.

(19) Fer, B. (2018d). Panel In: The Event of a Thread: Anni Albers conference.

(20) Craft Council. (2018). Continuing to Blaze a Trail [online]